That's right. I understand that many places only got to use the corrected ICEL translations last Sunday. I haven't noticed any blog reports of parishioners fainting, having palpitations, or any other adverse effects. There have been a very few hissy fits, but really these bear the tones of petulant toddlers, and seem to be making last-ditch attempts to persuade everyone that things will be really baaaaad if we use such big words.

That's right. I understand that many places only got to use the corrected ICEL translations last Sunday. I haven't noticed any blog reports of parishioners fainting, having palpitations, or any other adverse effects. There have been a very few hissy fits, but really these bear the tones of petulant toddlers, and seem to be making last-ditch attempts to persuade everyone that things will be really baaaaad if we use such big words.In Britain we have had the corrected translation since September. No-one died here, either.

I was asked to write about the introduction of the new texts from a layperson's perspective for the Catholic Herald, which included a special Advent Magazine last Sunday. I was tremendously chuffed to see that my name appeared on the front cover along with Monsignor Andrew Wadsworth and James MacMillan (Wow! Exalted company for me indeed!) Unfortunately, the Magazine isn't available online, so I can't just give you a simple link, but I thought I'd share what I wrote anyway...

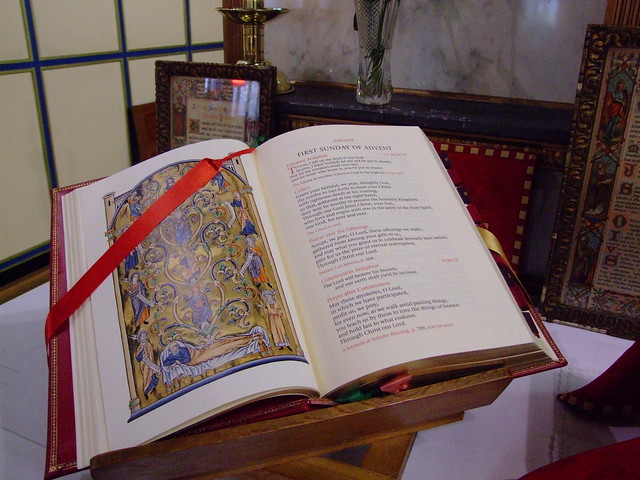

Liturgy: A golden age of worship.

I never learned Latin at school. As an adult, I would take great delight in reminding people that, for years, the only Latin in the Mass which I knew was the Kyrie eleison, and the rest was all Greek to me. And then I’d sit back and smirk as someone pointed out that the Kyrie actually was Greek. But not knowing any Latin meant that I had to rely on the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) translation of the Mass.

I never learned Latin at school. As an adult, I would take great delight in reminding people that, for years, the only Latin in the Mass which I knew was the Kyrie eleison, and the rest was all Greek to me. And then I’d sit back and smirk as someone pointed out that the Kyrie actually was Greek. But not knowing any Latin meant that I had to rely on the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) translation of the Mass.To begin with, this wasn’t a problem. But once I started to pray the Divine Office I became more and more aware that something wasn’t quite right. The collect at Sunday Mass and the concluding prayer for Morning and Evening Prayer bore a striking resemblance to each other. On looking at things more closely, I discovered that the prayers were actually supposed to be the same – they were the same in the Latin original – and so there was a difference in translation between the prayers for the Mass and for the Office.

I began to attend Mass in the Extraordinary Form and also to sing various parts of the Mass in Latin and, looking at the English translation, I became more and more aware that the language had been over-simplified, and words and phrases had been cut out. The Mass had been impoverished and it had lost the sense of the sacred. I also became aware that this was mostly a problem with the English translation. Most other languages seemed to stick much more closely to the Latin original, most noticeably with the "And with your Spirit" response. The English translation had rendered the phrase as "And also with you", turning it from a recognition of the sacerdotal character imprinted on the soul of the priest at Ordination to the equivalent of "And to you, too!"

Around this time, the news that a corrected translation was in the pipeline was being discussed, particularly on the internet. Fr John Zuhlsdorf, who writes for this newspaper, had a whole blog dedicated to accurate translation of the Latin texts at Mass in which the inaccuracies of the "lame-duck" ICEL translation were laid bare for everyone to see. A more accurate translation could only be a good thing, I thought, but I didn’t actually expect it to have much impact. After all, why should changing one or two words be that noticeable?

It also seemed to take such a long time to get under way. I couldn’t understand why translating the Mass should take so long, though I gathered from reading various reports that there were objections to the use of unfamiliar words. There was talk of the need for training courses to explain the new translation, especially for words such as "ineffable," "wrought" and "gibbet". I found this to be rather patronising. As a teacher, I am well aware that difficult words are only difficult until they are explained. After all, photosynthesis, chloroplasts and cytoplasm are quite difficult words too, but they are taught to every 11-year-old in their Science lessons.

As more and more people, especially on the internet, made fun of the objections and pointed out how spurious they were, I noticed that a real sense of excitement was starting to build. When the Bishops of England and Wales announced that, although the new translation would officially be mandated from the first Sunday of Advent this year, they wanted parishes to start using it from September to allow the laity to become familiar with the responses, it suddenly began to feel as though the change would really happen.

On the last Sunday in August, I attended Mass with a sense of an era coming to an end. The old ICEL translation was, after all, the only one I had ever known. Although I could hardly wait for the new version, it felt very strange indeed to realise that I would never again say "We believe…" I was almost nostalgic – but only almost.

At Mass the following week we had leaflets with the new responses typed out neatly. It was quite funny because our parish priest announced before Mass that the new responses would be used, and that sheets were available at the back of the church. A few people, having forgotten that this was the big day, shuffled out of their pews to collect a sheet. Mass began, and a few people stumbled over the automatic response "And also with you," and there was a little more shuffling as more people collected a sheet. Then the "I confess" provoked another bout of shuffling. By the time we got to the Gloria, the message appeared to have gotten through.

I felt a real thrill of excitement when making the new responses. At the "I confess" I was able to make the traditional threefold striking of the breast. Then, while reciting the Gloria, I saw how a whole section had been replaced, in which we give glory and praise to God, echoing the cry of the angels when they announced the birth of Christ. Why the words were ever left out in the old translation is a complete mystery – is it really possible to praise God too much?

It was very hard not to lapse into recitation of the Apostles’ Creed – the main indicator of which has always been "I believe," instead of the "We believe" of the Nicene Creed. There had been a great deal of fuss made of the proposed use of "consubstantial" in the Creed rather than "of one being", but actually I have always found the latter expression to be rather vague and woolly, whereas consubstantial quite simply means "of the same substance", and therefore it resonates more fully for me, expressing the divine nature of Christ.

But the most moving part of the new translation of the Mass for me was definitely in the Eucharistic Prayer. The words were unfamiliar, but at the same time they struck a chord. Suddenly it seemed clear that what was happening at the altar was the action of God, that the use of sacred language marked out the numinous for us: the priest, in persona Christi, was interceding on our behalf to the Father, and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is something done for us by God, not something we do for him.

It will take a while before I learn the new responses off by heart, and I am sure that I will make the occasional mistake. After all, I have been making the old responses for nearly 20 years. Nevertheless, it will be well worth the effort. The new translation has restored the sense of the sacred to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass.